Are Lithium-Ion Batteries Safe? What You Must Know About Battery Safety

Lithium-ion batteries have found their way into almost every corner of our daily lives: smartphones, tablets, Bluetooth earphones, drones, power tools, new energy vehicles, and energy storage systems.

At the same time, news reports about lithium battery fires and explosions appear from time to time, raising a common concern:

Are lithium-ion batteries really safe?

Where do the risks come from, and how can they be controlled?

In fact, lithium-ion batteries are not “inherently dangerous.”

The real challenge lies in how to firmly control safety while pursuing high energy density.

I. Why Is Safety So Critical for Lithium-Ion Batteries?

The greatest advantage of lithium-ion batteries is their high energy density, but this is also a double-edged sword.

The higher the energy density, the more energy is stored per unit volume or weight. Once a failure occurs, more energy is released in a short time.

In small consumer electronics, battery capacity is limited, and the total stored energy is relatively low. Even if a safety incident occurs, the impact is usually confined.

However, in large-capacity applications such as electric vehicles and energy storage systems, a single thermal runaway event can lead to severe consequences.

Therefore, safety has become one of the key factors limiting the further large-scale application of lithium-ion batteries.

II. What Do Lithium-Ion Battery Safety Tests Actually Test?

To reduce risks, lithium-ion batteries must pass a series of rigorous safety tests before leaving the factory and entering real-world applications.

Today’s mainstream testing systems mainly come from:

UL (Underwriters Laboratories, USA)

UN (United Nations transportation tests)

IEC (International Electrotechnical Commission)

The core purpose of these tests is straightforward:to simulate possible abuse scenarios in real life.

We introduced these tests in detail in previous articles. Common safety test items include:

Electrical performance tests: internal resistance, capacity ratio, cycle life, high- and low-temperature discharge

Safety performance tests: nail penetration, overcharge, overdischarge, external short circuit, thermal shock, flame exposure

Storage performance tests: room-temperature storage, high-temperature storage, casing stress tests

Environmental tests: altitude simulation, high-temperature and high-humidity storage, temperature cycling

Mechanical tests: compression, impact, acceleration shock, vibration, free fall

For example:

Nail penetration tests simulate internal short circuits

Overcharge tests simulate protection circuit failure

Altitude simulation tests correspond to air transportation environments

III. The Core Issue: Where Does the Heat Come From?

At its core, lithium-ion battery safety is essentially a thermal problem.

If the heat generated inside a battery cannot be dissipated in time, the temperature will continue to rise. Higher temperatures accelerate internal reactions, forming a vicious cycle—this is what we call thermal runaway.

Heat inside a battery mainly comes from three sources:

Heat from normal electrochemical reactions

Even under normal charging and discharging, batteries continuously generate heat.Heat from internal resistance and polarization

The higher the current and discharge rate, the more significant the heat generation.Heat from side reactions (the most dangerous source)

Once these reactions occur, they can directly trigger safety incidents.

In practice, it is often this third type that determines whether a battery becomes truly “dangerous.”

IV. What Dangerous Reactions Occur Inside the Battery?

1. Risks on the Cathode Side

Under high temperature or overcharge conditions, some cathode materials may decompose and even release oxygen.

This oxygen reacts violently with the organic solvents in the electrolyte, generating large amounts of heat and gas, which can easily trigger thermal runaway.

Different cathode materials show significant differences in this behavior.

2. Risks on the Anode Side

Graphite is currently the most widely used anode material. Under abnormal conditions, the anode may experience:

Decomposition of the SEI (solid electrolyte interphase) layer

Direct reaction between electrolyte and lithiated graphite

Reaction between lithiated graphite and the binder

These reactions not only release large amounts of heat but also generate gases such as CO and CO₂, rapidly increasing internal pressure.

If the temperature continues to rise, the anode active material may further react with the binder.

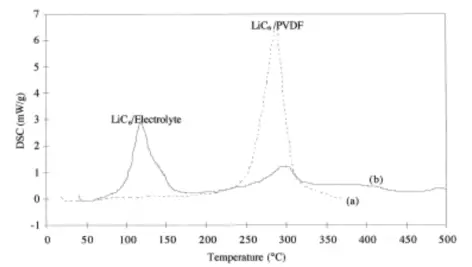

When PVDF is used as the binder, it can react with LiC₆ to form LiF and other products.

Ph. Biensan et al. studied these reactions using DSC and found that the reaction intensity is closely related to the presence of electrolyte.

Without electrolyte, this reaction releases a large amount of heat.

With electrolyte present, the heat from the reaction between LiC₆ and the electrolyte is more significant, while the reaction with PVDF releases less heat.

The reaction intensity is also related to the amount of PVDF present.

Du Pasquier et al. found that replacing pure PVDF with PVDF + HFP reduced the heat released from the binder–LiC₆ reaction by 23%.

H. Maleki et al. reported that when phenol-formaldehyde (PF) resin is used as the binder, the heat generated from the binder–LiC₆ reaction is almost negligible.

DSC curves of LiC₆/PVDF and LiC₆/Electrolyte

V. Which Cathode Materials Are Safer?

Based on extensive research and experimental data, different cathode materials show a clear ranking in terms of safety.

Considering oxygen release tendency, thermal stability, and electrolyte oxidation behavior, the general safety order of common cathode materials is:

Lithium iron phosphate (LFP)> Lithium manganese oxide (LMO)> Ternary materials (NCM/NCA)> Lithium cobalt oxide (LCO)> Lithium nickel oxide (LNO)

This explains why:

LFP is widely used in applications with extremely high safety requirements

High-nickel ternary materials offer higher energy density but face greater safety challenges

VI. Why Are Large-Capacity Batteries Harder to Make Safe?

One often-overlooked fact is that the larger the battery capacity, the harder it is to pass safety tests.

The reasons are simple:

Under the same abuse conditions, large-capacity batteries generate more heat

Once thermal runaway occurs, much more energy is released

That is why:

Consumer electronics batteries are relatively easier to certify

Safety design for power batteries and energy storage batteries is extremely complex

VII. Common Approaches to Improving Lithium-Ion Battery Safety

Today, the industry mainly improves safety from two directions: physical protection and chemical system optimization.

1. Physical Safety Measures

PTC thermistors

Fuses

Structural optimization and thermal management design

These measures can quickly cut off current or enhance heat dissipation under extreme conditions such as overcurrent or short circuit, preventing escalation.

2. Intrinsic Safety from Chemical Systems

Selecting safer cathode materials

Using anode materials with lower specific surface area

Optimizing electrolyte formulations and functional additives

Compared with “after-the-fact protection,” chemical system optimization improves safety at the source.

VIII. Safety Is Always the Bottom Line for Lithium-Ion Batteries

As lithium-ion batteries continue to evolve toward higher energy density and larger capacity, safety will only become more critical.

A truly excellent battery solution never blindly pursues specifications alone—it seeks the optimal balance between performance, lifespan, and safety.

Safety is not a selling point.It is the bottom line.