To what extent must the electrolyte be insufficient before it starts to affect the cell’s performance?

When a lithium-ion battery has insufficient electrolyte, it’s just like a person getting sick—minor issues may seem harmless, but severe ones can directly threaten its “life.” So what exactly happens to cell performance when electrolyte is lacking? What’s the difference between a slight shortage and a severe shortage? In this article, the editor from Iray Energy will explain the problem from three levels: “slightly low,” “low,” and “severely low,” to help you fully understand the issue.

A quick note: since different battery materials and manufacturing processes lead to different electrolyte uptake levels, the descriptions here only provide qualitative definitions of electrolyte deficiency.

1. Slightly Insufficient Electrolyte: A Hidden and Latent Issue

Even if the electrolyte is only “slightly” insufficient, the cell should already be considered problematic. Why? Because the shortage may come from insufficient injection during production, or from insufficient aging time, preventing the electrodes from becoming fully wetted. On the surface, capacity and internal resistance may still look normal, making the issue hard to detect—just like a spy hiding in the dark.

So how can we identify a cell with mildly insufficient electrolyte? There are three main methods:

1) Disassembling the cell:

This is the most direct method, allowing you to see immediately whether the interior lacks electrolyte. However, it is a destructive test, meaning only one cell can be evaluated at a time, making it nearly impossible for mass production.

2) Weight measurement:

In theory, weighing can detect electrolyte-deficient cells. The problem is that the cell also contains electrodes, aluminum-laminated film, and other components, all of which have their own weight variations. Since the difference caused by slightly insufficient electrolyte is extremely small, it is easily masked by these variations. The only effective approach is measuring injection volume or electrolyte retention in real time, which depends on process control rather than post-production weighing.

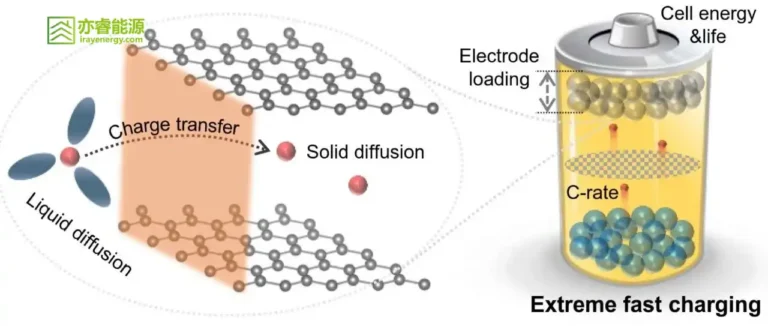

3) Testing electrochemical performance:

This is the most crucial method. Cells with slightly insufficient electrolyte may show normal capacity and internal resistance in the beginning, but issues will emerge when tested using cycling or high-rate discharge platforms. Cycling tests show that these cells may behave normally for the first few dozen cycles, but their capacity will suddenly “drop sharply” afterward. The phenomenon is that a large amount of charge can still be stored, but the discharged capacity is significantly lower, with a charge-discharge efficiency greater than 1. After the sudden drop, the capacity will not go directly to zero, but stabilize at about 20%–40% of its initial capacity.

High-rate discharge testing is even more revealing. For example, at 1C or 2C discharge rates, cells with sufficient electrolyte will show about 8% higher capacity compared to those with slightly insufficient electrolyte. This method can be used effectively in mass-production screening—provided the cells themselves have good consistency; otherwise, the differences could be obscured.

Overall, when the electrolyte is slightly insufficient, the cell carries significant latent risks. These issues become apparent mainly during long-term cycling or high-rate usage.

2. Electrolyte Shortage: A High-Risk Intermediate State

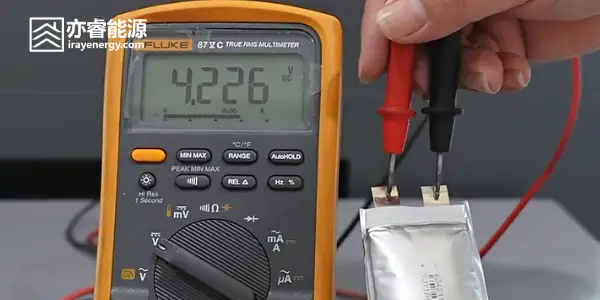

The condition of “shortage” is more pronounced than “slightly insufficient,” with the most typical characteristic being elevated internal resistance. At this stage, the capacity may still appear normal, but both cycling performance and high-rate discharge platform capacity are significantly worse than those of normal cells.

In one experiment involving the self-discharge measurement of 110 mass-production cells, several cells were found to have normal capacity but abnormally high internal resistance (it was precisely through analyzing this dataset that the article “7 Perspectives to Uncover the Truth Behind Self-Discharge“, which systematically explains the causes of low voltage in batteries, was written). When these cells were further tested on the high-rate discharge platform, their capacities were noticeably lower than those of cells with normal internal resistance. Cycling tests could not even proceed normally—during charging and discharging, the protection circuitry was triggered very quickly. When this type of cell is disassembled, it may even catch fire during outdoor handling!

The problems associated with “electrolyte shortage” are essentially an upgraded version of those seen in “slightly insufficient” electrolyte cases. Not only do the cycling and high-rate risks remain, but there is also an obvious abnormality in internal resistance, making such cells relatively easier to screen—internal resistance is already a parameter manufacturers monitor closely.

Overall, although a cell with insufficient electrolyte has not completely failed yet, once put into use, both the safety hazards and the risk of performance degradation are already very high.

3. Severe Electrolyte Shortage: A Full-Blown Performance Collapse

When the electrolyte level drops to the point of being “severely insufficient,” the problems become extremely obvious: low capacity, high internal resistance, poor cycling performance, and low platform capacity — nearly all performance indicators show abnormalities.

The most direct and visible result of severe electrolyte deficiency is low capacity. When a poorly manufactured cell suffers from inadequate capacity due to severe electrolyte shortage, there is almost no way to fix it. The cycling performance and high-rate capability also deteriorate significantly; after charging, the cell may lose 10% of its capacity within a short period of time, and its thickness may increase abnormally as well.

A more severe issue arises when the electrolyte is seriously insufficient, as it may also lead to uneven electrolyte absorption between the positive and negative electrodes:

Insufficient absorption on the positive electrode: The positive electrode provides fewer lithium ions, but the negative electrode absorbs electrolyte sufficiently and can accept lithium ions; overall, the cell appears “dry” but without lithium plating.

Insufficient absorption on the negative electrode: The positive electrode functions normally, but the negative electrode cannot receive lithium ions, making lithium plating likely; overall performance shows low capacity, high internal resistance, low discharge platform, and poor cycling.

Cells in this condition can easily catch fire when disassembled, so they must be strictly avoided during mass-production screening.

Summary

Based on the above analysis, we can see that the impact of electrolyte deficiency on cell performance is progressive and hierarchical:

Slightly Low: Capacity and internal resistance appear normal in the early stage, but the potential risks are significant. Problems become apparent during cycling and high-rate usage.

Low: Internal resistance increases, cycling performance and rate capability decline, and safety risks become more prominent.

Severely Low: Low capacity, high internal resistance, poor cycling, poor platform performance—almost all indicators deteriorate, and safety risks may arise.

Just like an illness in the human body, mild symptoms may not be obvious at first, while severe problems erupt all at once. It’s the same with cells suffering from electrolyte deficiency—a minor issue, if ignored, can accumulate into a serious hidden danger.

For battery manufacturers, the most important approach is still to control filling volume and absorption from the source and ensure every cell is fully “soaked” with electrolyte. This is far more reliable than relying on post-production testing and screening.