7 Key Points That Determine Lithium-Ion Battery Cycle Performance

How long can the cycle life of a lithium-ion battery actually reach? Is it 300 cycles, 500 cycles, or over a thousand cycles? This is a fundamental question that every professional in battery R&D, quality, manufacturing, and sales must face.

The cycle performance of a battery depends not only on the materials themselves, but also on how well the production details are controlled. Cycle life is one of the most critical and most complex performance indicators in the lithium-ion battery industry. Many factors are involved, and their interactions are complicated. In many cases, poor cycle performance does not stem from a single issue, but from a “chain reaction” caused by multiple factors stacking together.

Below, we will examine seven key factors that influence the cycle performance of lithium-ion batteries.

1. Choosing the Wrong Materials Can “Sentence” Cycle Life to Death from the Start

Raw materials are the starting line for battery cycle life. If the materials are chosen incorrectly, no amount of process optimization afterward can save the performance.

For example, lithium manganese oxide, lithium cobalt oxide, lithium titanate, and NCM/NCA ternary materials all have inherently different levels of structural stability. Even within the same ternary system, different suppliers, coating methods, and surface treatments can lead to significant differences in cycle performance.

Material-related issues that affect cycle life mainly fall into two categories:

• Structural degradation occurs too quickly:

During lithium insertion and extraction, large lattice changes can cause the material to gradually fracture and lose contact, resulting in rapid capacity fade.

• Poor SEI formation:

Especially on the anode—if the SEI is not dense and stable, it will continuously react with the electrolyte. The more it reacts, the less electrolyte remains, and the worse the cycle performance becomes.

In short:

The cycle life of a battery is ultimately determined by the weakest link between “cathode + electrolyte” and “anode + electrolyte.”

2. Excessive Electrode Compaction Can Cause Mid-Cycle “Cliff-Drop” Performance

What’s the benefit of high compaction?

Higher energy density.

What’s the downside?

Cycle performance tends to decline.

The impact of compaction on cycle life mainly comes from two mechanisms:

• Material damage:

The higher the compaction, the more the active particles are forcibly compressed. Their internal structure becomes stressed and is more likely to crack during cycling.

• Reduced electrolyte retention:

When compaction is too tight, electrolyte cannot penetrate well, wets the electrode slowly, and results in insufficient formation. Once cycling starts, the hidden problems quickly emerge.

Too loose is also not acceptable—energy density cannot be achieved. Too high leads to poor cycle performance, too low leads to insufficient energy density.

This is why compaction degree is always one of the most difficult trade-offs in battery R&D.

3. Excess Moisture Gradually “Eats Away” the Cycle Life

Moisture is a major enemy of lithium-ion cells, which is why strict control of temperature and humidity during production and material handling is essential.

So what happens when moisture exceeds the limit?

Its impact is mainly reflected in the following areas:

• Structural damage to the cathode and anode materials

• Accelerated decomposition of the electrolyte

• Interference with proper SEI formation

• Increased risk of lithium metal deposition

4. Improper Coating Areal Density Can Cause Mid-Cycle Performance Fluctuations

Many people focus solely on capacity and energy density, overlooking how coating areal density affects cycle performance. So, how does areal density influence cycling?

Low areal density → more electrode layers → more separators → more electrolyte absorption → relatively more stable cycling

High areal density → fewer electrode layers → fewer separators → less electrolyte absorption → relatively worse cycling

Potential issues with too low areal density:

Coated electrodes are more likely to have surface particles; after calendering, particle locations can be crushed

Coating uniformity is more difficult to achieve

Potential issues with too high areal density:

Higher compaction leads to higher internal stress within the electrode

Electrolyte infiltration takes longer

Therefore, areal density is not simply a matter of “higher or lower”; it must be optimized according to material characteristics and the target application.

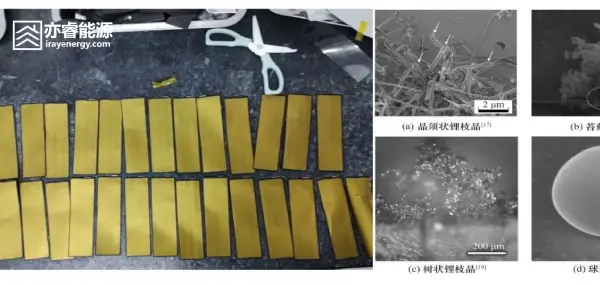

5. Insufficient Anode Excess Can Cause Late-Stage “Cliff-Drop” in Cycle Life

Early cycles may appear normal, but after a few hundred cycles, performance can suddenly collapse—this is the most common “late-stage cliff-drop” phenomenon in battery cycling.

The core reason lies in insufficient anode excess.

Why does this happen? Mainly for the following reasons:

The anode undergoes structural changes faster than the cathode during cycling

Once the anode capacity fades, it cannot fully accommodate all the lithium released by the cathode

The excess lithium can only deposit on the anode surface as metallic lithium (lithium plating)

Once lithium plating occurs, the SEI continuously reforms → accelerating electrolyte consumption

Therefore, anode excess is not only a matter of “safety”; it is a critical factor in maintaining stability during the later stages of cycling.

6. Insufficient Electrolyte Can Cause Gradual Late-Stage Cycle Decay

Many cells with poor cycle performance are not failing because of the materials or the process—they are failing because there isn’t enough electrolyte. Electrolyte shortage mainly comes from three sources:

Designed injection volume is insufficient

Under-filling during the electrolyte injection process

Excessive compaction, resulting in incomplete electrolyte infiltration

The third point is often the most overlooked.

If the SEI layer is unstable, it will continuously reform during cycling, leading to:

Depletion of reversible lithium

Continuous electrolyte consumption

Electrolyte dry-out in the later stages

Many cells that collapse after only a few dozen cycles can see significant improvement simply by increasing electrolyte retention slightly.

The impact of electrolyte on cell performance has been previously discussed in “To what extent must the electrolyte be insufficient before it starts to affect the cell’s performance?”, so it will not be elaborated here. For those interested in learning more about how electrolyte affects cycling, please refer to that article.

7. Non-Standard Cycle Testing Conditions Can Cause “False Poor” or “False Good” Results

Cycle testing is not simply a matter of putting the cell into a tester and pressing start. Environmental conditions and test parameters directly affect the results. The following factors can cause significant deviations in cycle data:

Inconsistent cut-off voltages

Inconsistent charge termination currents

Large fluctuations in test temperature and humidity

High contact resistance → actual current rate higher than intended

Test interruptions → system re-evaluates the cell state

Overcharging or over-discharging

Therefore, sometimes poor cycle performance is not caused by the battery itself, but by variations in test conditions.

To meaningfully compare cycle life, the prerequisite is that testing conditions must be controlled, standardized, and consistent.

Summary

There are many factors that affect cycle life, but like the “wooden barrel principle”:

It is not the average level that determines cycle life, but the shortest plank among all factors.

Raw material combinations and batches must be stable, compaction must be appropriate, moisture must be low, electrode areal density must be reasonable, anode excess must be sufficient, electrolyte must be adequate, and testing must be standardized. These factors do not exist independently—they interact and constrain each other.

Achieving excellent cycle performance in a battery is not about optimizing a single point to perfection; it is about making sure no mistakes are made in any of the key factors.